Table of Contents

Introduction

As networks grow, managing multiple customers, branches, or environments on the same infrastructure becomes challenging, especially when IP addresses overlap. This is a common real-world problem faced by network engineers in service providers and enterprise networks.

In this article, we will learn what VRF (Virtual Routing and Forwarding) is, why it is needed, and how it helps isolate routing tables on a single router. We’ll understand VRF using simple explanations and real-life scenarios so the concept feels practical, not theoretical.

Now, let’s begin with the basics.

What exactly is VRF?

The Networking Superpower That Saves You from IP Address Nightmares

If you’ve ever worked on a real network, especially one that connects multiple customers, branches, or environments, you’ve probably hit this wall:

“Why are these IPs overlapping… and why is everything broken now?”

That’s where VRF (Virtual Routing and Forwarding) quietly steps in and saves your sanity.

VRF is one of those technologies that sounds intimidating at first, but once it clicks, you wonder how networks ever survived without it. In simple terms, VRF allows a single physical router to behave like multiple independent routers, each with its own routing table, own interfaces, and own routing protocols, all completely isolated from each other.

- Think of VRF as VLANs for Layer 3.

- VLANs separate broadcast domains on switches.

- VRFs separate routing domains on routers.

Life Without VRF: One Routing Table to Rule Them All

By default, every router maintains one global routing table.

Every interface you configure, physical or logical, feeds routes into that single table. This works fine until the real world shows up.

Let’s say you try this:

Interface Gi0/0 → 10.1.1.1/24

Interface Gi0/1 → 10.1.1.1/24Boom.

The router shuts you down instantly with an overlapping IP address error.

Why? Because the router has no way to distinguish between identical networks inside the same routing table. To it, 10.1.1.0/24 is 10.1.1.0/24. End of discussion.

Now imagine you’re a service provider or even a large enterprise, and multiple customers or departments are all using the same private IP ranges.

That’s not a theoretical problem.

That’s daily life.

Real VRF Use Case

I still remember my first serious encounter with VRF in a lab. Two customer networks. Both shouting:

“My subnet is 10.1.1.0/24!”

The PE router was having none of it.

Then I created two VRFs:

- VRF-CustomerA

- VRF-CustomerB

Assigned one interface to each VRF.

- Same IP subnet

- Same router

- Zero conflict

It felt like cheating—except it was clean, elegant engineering. That’s the magic of VRF.

Why Service Providers Absolutely Depend on VRF

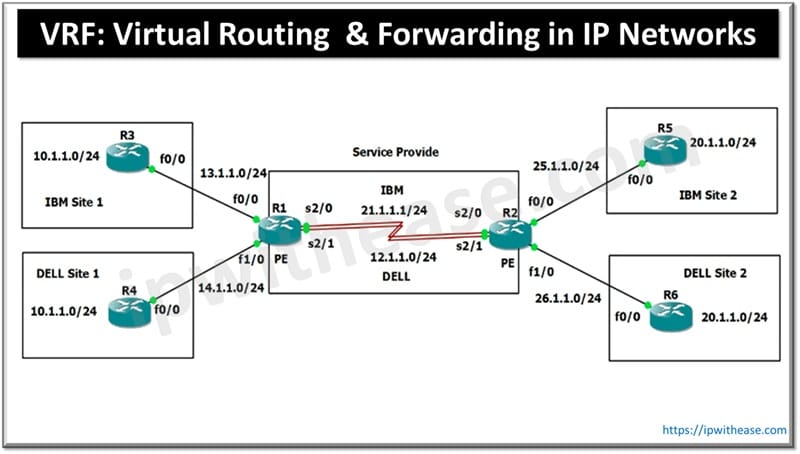

Let’s walk through a real-world service provider scenario. You’re an SP connecting branch offices for multiple companies.

Customer 1: IBM

Site 1: 10.1.1.0/24

Site 2: 10.1.2.0/24

Customer 2: Dell

Site 1: 10.1.1.0/24

Site 2: 10.1.2.0/24

Yes. Same IPs, same subnets, different customers.

Your PE routers (R1 and R2) sit in the middle, learning routes via OSPF, EIGRP, or BGP.

What Happens Without VRF?

Both IBM and Dell advertise identical prefixes. The router compares Administrative Distance.

EIGRP (90) beats OSPF (110).

One customer’s routes win.

The other customer disappears.

Result?

Customers can’t reach their own branches.

That’s not just bad networking—that’s a support ticket apocalypse.

Enter VRF: Clean Separation, Zero Drama

With VRF, the solution becomes almost boringly simple.

On the PE router:

IBM’s CE interface → VRF-IBM

Dell’s CE interface → VRF-Dell

Now the router maintains two completely separate routing tables.

VRF-IBM Routing Table

10.1.1.0/24 (local)

10.1.2.0/24 (learned from remote PE)

Core transport routes

VRF-Dell Routing Table

Same prefixes

Same metrics

Totally isolated

Traffic entering an IBM interface is forced to use the IBM routing table.

Dell traffic never even sees it.

Same router.

Parallel universes.

VRF and VLANs: The Mental Model That Makes It Click

If you’ve ever configured router-on-a-stick, you already understand VRF at a conceptual level.

With VLANs, one physical interface becomes many logical ones:

interface Gi0/0.10

encapsulation dot1Q 10

ip address 10.1.10.1 255.255.255.0

!

interface Gi0/0.20

encapsulation dot1Q 20

ip address 10.1.20.1 255.255.255.0Each VLAN is isolated at Layer 2.

VRF does the same thing—but at Layer 3, and without VLANs.

ip vrf CustomerA

rd 1:1

!

interface Gi0/0

ip vrf forwarding CustomerA

ip address 1.1.1.1 255.255.255.0That interface now only exists inside CustomerA’s routing universe.

Routing Protocols Inside VRFs: No Cross-Talk Allowed

Another underrated superpower of VRF:

Routing protocols run per VRF.

You can run:

EIGRP in one VRF

OSPF in another

BGP in a third

All on the same router.

Each VRF has:

- Its own neighbors

- Its own topology database

- Its own routing decisions

The global routing table stays clean, handling only provider core infrastructure.

One Core Link, Thousands of Customers: How This Actually Scales

Now comes the part that feels like black magic the first time you see it.

You can’t run a physical link per customer between PE routers. That doesn’t scale.

So service providers use:

- MPLS

- MP-BGP

- Route Distinguishers (RD)

- Route Targets (RT)

- Route Distinguisher (RD): Making Routes Unique

RD takes a normal IPv4 prefix and makes it globally unique.

Example:

10.1.1.0/24

RD: 65001:1

Becomes:

65001:1:10.1.1.0/24This new address family is called VPNv4.

MP-BGP carries these VPNv4 routes between PE routers, even if the IPv4 parts overlap.

MPLS: The Unsung Hero in the Data Plane

Once the control plane figures out where traffic should go, MPLS handles forwarding.

Customer Packets:

- Enter PE

- Get labeled

- Cross the core

- Exit at the correct PE

- Labels stripped

Delivered to the correct VRF. Core routers never see customer IPs. They just switch labels. That’s how privacy and scale coexist.

A Practical VRF Configuration Walkthrough (Cisco IOS-XE)

Here’s a simplified but realistic configuration.

Step 1: Create VRFs

ip vrf IBM

rd 65001:1

route-target export 65001:1

route-target import 65001:1

!

ip vrf Dell

rd 65001:2

route-target export 65001:2

route-target import 65001:2Step 2: Assign Interfaces

interface Gi0/0/0

ip vrf forwarding IBM

ip address 1.1.1.1 255.255.255.0

!

interface Gi0/0/1

ip vrf forwarding Dell

ip address 1.1.1.1 255.255.255.0Yes. Same IP, different VRFs.

Step 3: Customer Routing

router eigrp 100 vrf IBM

network 1.1.1.0 0.0.0.255

!

router eigrp 200 vrf Dell

network 1.1.1.0 0.0.0.255Step 4: MP-BGP for MPLS VPN

router bgp 65001

address-family vpnv4

neighbor 2.2.2.2 activate

!

address-family ipv4 vrf IBM

redistribute eigrp 100

Mirror this on the remote PE, and you’re in business.Common VRF Mistakes (We’ve All Made Them)

Let’s save you some pain.

Forgot ip vrf forwarding

Routes land in the global table.

Check:

show ip vrf interfaces

RD / RT mismatch

Routes appear in BGP but not in the VRF routing table.

MPLS not working

No labels = no traffic.

show mpls forwarding-table

Same RD for multiple VRFs

Congratulations, you just merged customers.

Pro Tip

Test like a pro:

ping vrf IBM 10.1.2.1 source 1.1.1.1

VRF Beyond Service Providers

VRF isn’t just an ISP thing.

Enterprises use VRF for:

- Finance vs HR isolation

- Dev / staging / production separation

- Lab environments in GNS3 or EVE-NG

- Post-merger IP conflicts

- Zero-trust segmentation

I’ve personally seen VRF save hundreds of thousands in hardware costs by collapsing multiple routers into one.

Final Thoughts: Why VRF Is a Must-Have Skill

VRF isn’t flashy. It doesn’t blink LEDs. It won’t trend on social media. But it quietly powers:

- MPLS L3VPNs

- Large enterprise cores

- Cloud-scale multi-tenancy

If you understand VRF, you understand modern networking design. And once you truly get it, overlapping IPs stop being a nightmare, and start being just another solved problem.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

You can learn more about her on her linkedin profile – Rashmi Bhardwaj